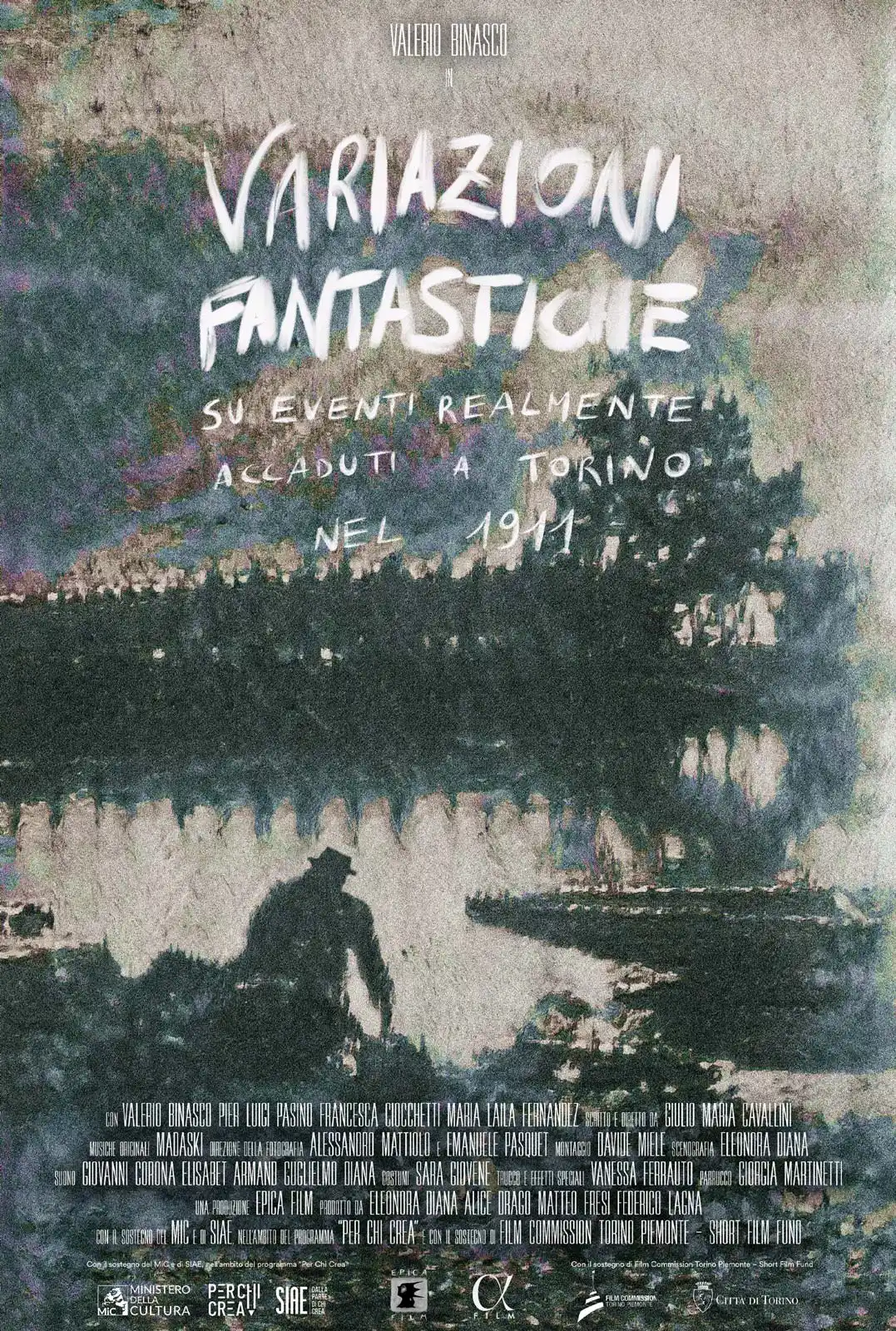

fantastic variations on events that really happened in turin in 1911

(Variazioni fantastiche su eventi realmente accaduti a Torino nel 1911)

by Giulio Maria Cavallini

short film | drama

A double showdown looms over Emilio Salgari: the exhaustion of his creativity and the realization that he has destroyed his wife Ida's life.

Synopsis

fantastic variations on events that really happened in turin in 1911

(Variazioni fantastiche su eventi realmente accaduti a Torino nel 1911)

by Giulio Maria Cavallini

short film | drama

A double showdown looms over Emilio Salgari: the exhaustion of his creativity and the realization that he has destroyed his wife Ida's life.

Synopsis

Fantastic variations on events that really happened in Turin in 1911

( Variazioni fantastiche su eventi realmente accaduti a Torino nel 1911 )

Italy, 2025 / 20′

a film by

Giulio Maria Cavallini

with

Valerio Binasco

Pier Luigi Pasino

Francesca Ciocchetti

Maria Laila Fernandez

| Written and Directed by | Giulio Maria Cavallini |

| Director of Photography | Alessandro Mattiolo Emanuele Pasquet |

| Production Design | Eleonora Diana |

| Costume Design | Sara Giovene |

| Make-Up | Vanessa Ferrauto |

| Editing | Davide Miele |

| Composer | Madaski |

| Sound | Giovanni Corona Elisabet Armand Guglielmo Diana |

| Producers | Alice Drago Eleonora Diana Federico Lagna Matteo Fresi |

| Production | Epica Film |

| Distribution | Alpha Film |

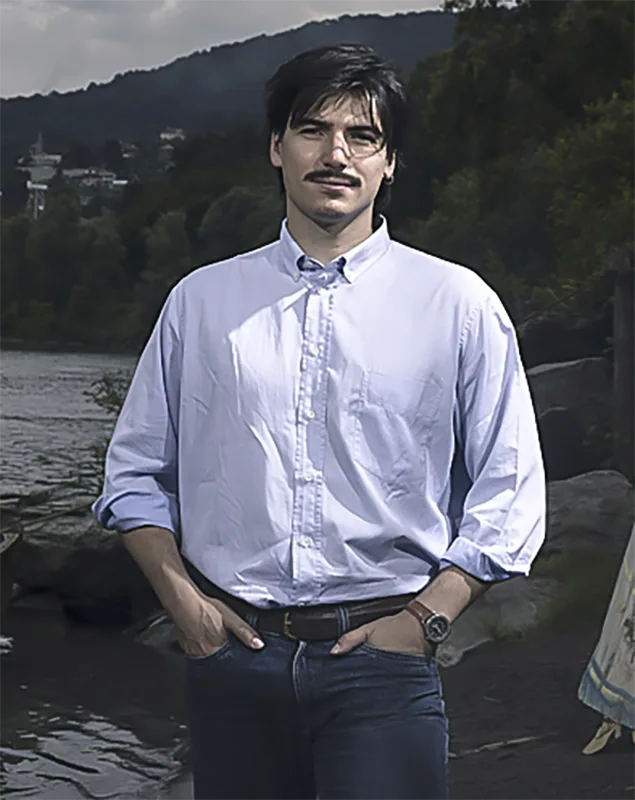

The Director

Giulio Maria Cavallini

Biofilmography

Giulio Cavallini is an Italian director, photographer, and actor. He was born in Turin in 1993 and began acting at the age of 15, attending the Sergio Tofano Theatre School. Then he became a student at the Professional Training School for Actors of the Teatro Stabile di Torino, graduating in 2015. He is the author, director, and producer of various short films, including “Il sognatore” (2011), which won the Jury Prize at the Sottodiciotto Film Festival, and “Conseguenze” (2017). In 2021, he wrote, directed, and acted in the short film “Ratavoloira”, screened out of competition at the 39th Torino Film Festival. In theater, he is the author and director of the play “#max²”, which debuted in 2016 at the Cavallerizza Reale Occupied Space in Turin. In 2020, he was among the finalists for the Venice Biennale’s Under 30 Directors’ competition.

Filmography:

- “Variazioni fantastiche su eventi realmente accaduti a Torino nel 1911” (2025)

- “Ancora Ieri” (2023)

- “All’imbrunire” (2021)

- “Ratavoloira” (2021)

- “Blackbird” (2020)

- “Conseguenze” (2017)

- “Niente di grave” (2014)

- “Lo Sconosciuto” (2013)

- “Gabriele” (2013), co-regia con Aliosha Massine

- “Il sognatore” (2011)

Director statement

We know from his son Omar that Salgari wrote not three but thirteen farewell letters, ten of which mysteriously disappeared. He penned them on April 22, but did not take his life until three days later, on April 25. It is a peculiar fact to write farewell letters 48 hours before enacting the announced intention. How did Salgari spend those 48 hours between writing the letters and the morning of his death? Perhaps he visited his hospitalized wife at the asylum, and this vision delivered the final blow? More likely, his entire life, with its misfortunes, small glories, and many regrets, surged back over him like a wave.

While there have been numerous adaptations (cinematic, television, theatrical, radio…) of Salgari’s works, it is true that the same attention has not been given to their author. The human story of Emilio and Ida Salgari binds these two figures symbolically to the history of Turin, while also carrying universally resonant symbolism. The volume and nature of the documents studied established a direct cause-and-effect link between Ida’s institutionalization—escorted to the asylum by public forces on April 19, 1911—and Emilio’s suicide on April 25. In other words, the Captain only ended his life when he lost his Aida. The documents also revealed that Ida assisted her husband in crafting his novels—a completely new revelation—bringing forth a poignant figure of quiet yet compelling biographical stature, marked by the same mix of grandeur and misery as the Captain and a deeply intense feminine tragedy.

These are suspended and magical hours spent along the “wild” banks of the Po near the Madonna del Pilone, a space Salgari had transformed into a laboratory and stage for his boundless creativity.

The film bears significant continuity with my previous experiences: firstly, I graduated from the Teatro Stabile di Torino’s School, where the protagonist, Valerio Binasco—one of Italy’s most acclaimed and awarded theater artists—was my teacher before becoming the theater’s director; secondly, all my cinematic works have been influenced, one might say, by theater. Another essential aspect for me is the photographic vision; since my earliest readings of Salgari, the Captain’s words have profoundly stimulated my photographic imagination (in a way, Salgari was a filmmaker and a precursor of television through the visual precision of his writing). The concept of having the weary, depressed author converse with cardboard cutouts of the characters and heroes he created is a poetic interpretation that I am certain can engage even those unfamiliar with his story, and hopefully lead them to rediscover his literature.

During his conversation with the Civic Guard, Emilio will admit the most startling truth about his novels and his writing process: “I’ve never been to Malaysia, India, Africa… It has always been a stage to lend more credibility to my novels,” thus revealing, to the shock of the Civic Guard and all those new to Salgari’s work, the talent of a writer-magician-manipulator of dreams, who became the literary phenomenon he is today (ironically dissected by academia only after ceasing to be a mass phenomenon).

Salgari, however, was not inspired by some joyous divine grace from his imagination; he constructed his texts through an impressive body of research. Throughout his life, he filled dozens of notebooks with notes taken from the Civic Library of Turin, gathering the building blocks of his stories. His material held geographical and historical validity; he invented nothing, never traveled, and reworked everything with exhausting effort that, in a way, killed him, as did the chasm between his 158 centimeters of height, the misfortunes of his life, and the fantastic world he created, of which he became a prisoner. The last of the cruel misfortunes was the theatrical enactment of his brutal suicide in a Turin exultant for the Great Exhibition. The death of one of the greatest and most renowned writers of the twentieth century was thrown in the world’s face, yet went unnoticed.